The emergence of cash distributions in the civic euergetism of the Roman imperial east*

La aparición de las distribuciones monetarias en el evergetismo cívico del Oriente imperial romano

Marcus Chin**

University of Oxford

Abstract: Individualised distributions of money by civic benefactors, in the form of coinage, were a common feature of public life in Greece and Asia Minor under Roman imperial rule, from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. However, the chronological specificity of this practice, as opposed to the distribution of other types of commodities (e.g. grain, oil), has not often been noticed. This paper first suggests that public euergetic distributions of coinage only seriously emerged as a social phenomenon in the early 1st century CE, before relating their emergence from this point to several factors inherent to the transformation of the Roman state at this time: the influence on the local elite of imperial ideology, particularly in cash handouts carried out at Rome, and developments in the monetary and fiscal history of the region. The rise of cash handouts thus presents an insight into the impact of Roman domination on local cultural practice.

Keywords: Civic euergetism, public distributions, Roman Greece, Roman Asia Minor, coinage, taxation.

Resumen: Las distribuciones individualizadas de dinero por parte de los benefactores de las ciudades, en forma de moneda, constituían una característica habitual de la vida pública en Grecia y Asia Menor durante el Imperio Romano, entre los siglos i-iii d. C. Sin embargo, raramente se ha puesto en valor la cronología específica de esta práctica, en oposición a distribuciones de otro tipo de materias (por ejemplo, grano, aceite). En este artículo se sugiere por primera vez que las distribuciones públicas de moneda tan solo aparecieron seriamente a comienzos del siglo i d. C., y después se relaciona esta novedad a partir de ese momento con varios factores inherentes a la transformación del estado romano en ese periodo: la influencia de la ideología imperial sobre las élites locales, sobre todo con las distribuciones de dinero efectuadas en la propia Roma, y el desarrollo en la historia monetaria y fiscal en la región. El auge de las distribuciones de moneda presenta, por tanto, una revelación del impacto del dominio romano en las prácticas culturales locales.

Palabras clave: Evergetismo cívico, distribuciones públicas, Grecia romana, Asia Menor romana, moneda, fiscalidad.

* I would like to thank the participants of the seminar held at Vitoria-Gasteiz in October 2023: Cédric Brélaz, David Espinosa Espinosa, Piotr Głogowski, Andoni Llamazares Martín (in particular for translating the abstract) and Elena Torregaray, as well as Leah Lazar, the anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Veleia, for their helpful comments and assistance in the preparation of this article. Work on it was supported by funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 865680, «CHANGE. The development of the monetary economy of ancient Anatolia, c. 630-30 BC.»).

** Correspondence to: Marcus Chin, University of Oxford, Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Ioannou Centre for Classical & Byzantine Studies, 66 St. Giles’, OX1 3LU, Oxford – marcus.chin@classics.ox.ac.uk – http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0573-9341.

How to cite: Chin, Marcus (2025), «The emergence of cash distributions in the civic euergetism of the Roman imperial east», Veleia, 42, 43-75. (https://doi.org/10.1387/veleia.25841).

Received: 2023 december 18; Final version: 2024 may 24.

ISSN 0213-2095 - eISSN 2444-3565 / © 2025 UPV/EHU Press

![]() This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

Introduction

The subject of this paper is a significant but perhaps easily overlooked aspect of civic life in the Roman imperial east, chiefly attested in the epigraphic remains of the Aegean basin and Asia Minor. It crops up, for instance, in a late 2nd-century CE dedicatory inscription from Syros commemorating the stephanephoros Antaios son of Modestus, who[1]

…ἔδωκεν [ἑ]|[κάστ]ῳ σφυρίδος δηνάρια πέντε, ἐλευ[θέ]|[ραι]ς δὲ γυναιξὶν πάσαις καὶ θηλείαι[ς] | [παισὶν] οἶνον· καὶ ἔδωκεν ταῖς μ[ὲν γυ]|[ναιξὶ] διανομῆς ἀνὰ ἀσσάρια ὀ[κτώ], | [ταῖς δὲ] παισὶν ἀνὰ ἀσσάρια τέσσα[ρα· τῇ] | [δὲ ἑξῆς] ἡμέρᾳ παρέσχεν τοῖς μὲν γε]|[ρουσιασ]ταῖς καὶ ἄλλοις οἷς ἐβουλήθ[η] | [δεῖπνο]ν καὶ ἔδωκεν ἑκάστῳ διαν[ομῆς] | [ἀνὰ δην]άριον ἕν· τοῖς [δὲ] λοιποῖς πολεί|[ταις καὶ πα]ισὶν ἐλευθέρ[οι]ς καὶ πα[ρ]οικο[ῦσι] | [παρέσχεν] οἶνον καὶ ἔδωκεν διανομῆ[ς] | [τοῖς μὲν π]ολείταις ἀνὰ δηνάριον ἕν, [ἐλευ]|[θέροις δὲ] παισὶν ἀνὰ ἀσσάρια ὀκτώ…

…gave five denarii to each (gerousiastes) in lieu of a basket-lunch, and wine to all the free women and girls; he gave eight assaria to each woman as a distribution, and four assaria to each child. On the following day he prepared a dinner for the gerousiastai and others whom he wished, and gave to each, as a distribution, one denarius; to the other citizens and free children and paroikoi he provided wine, and gave to each citizen, as a distribution, one denarius, and to the free children eight assaria…

This is the culture, among the wealthiest strata of the civic elite, of distributing monetary gifts —making cash handouts— in the form of coins, to individuals of specified social groups. Alongside distributions of other types of gifts and commodities (grain, oil, or wine, especially at festal banquets), such monetary distributions took place at festivals, the dedication of an honorific statue, as part of the promise of an elected office-holder (as here), or sometimes simply as a benefaction on its own, and are most widely attested from the late 1st to mid-3rd centuries CE[2]. They have largely been examined within the wider phenomenon of public distributions more generally, as reflecting a shift towards social hierarchisation in the imperial period, and the role of powerful benefactors in re-defining the terms of civic participation and identity[3]. Less attention, however, has been paid to the sheer fact that cash handouts involved the distribution of coin. Amidst larger debates about the sociology of euergetic gift-exchange, it has been easy to take this monetary character for granted, almost as a natural product of the generosity of the wealthy: whether cash or commodity has been unimportant, because the main point was that the act of giving initiated reciprocal exchange, generated honour, and perpetuated memory[4].

Coinage was uniquely versatile in representing both a commodity and monetary currency, and was perhaps even the most elegant tool for defining, in calculable form, the inequalities between the elite and non-elite essential to euergetism[5]. The very emergence of its use in public distributions, however, comprises an illuminating episode in cultural change in the eastern Mediterranean, because euergetic cash handouts are attested virtually only from the 1st century CE onwards. The present discussion considers how and why this was the case. The first section surveys the earlier history of euergetic public distributions, revealing the novelty of the use of coinage as a medium of distribution in the early imperial period; the second and third sections then provide explanatory contexts for this finding, in the influence of imperial ideology, and developments in monetary and fiscal history in the Roman east.

1. From non-monetary to monetary distributions

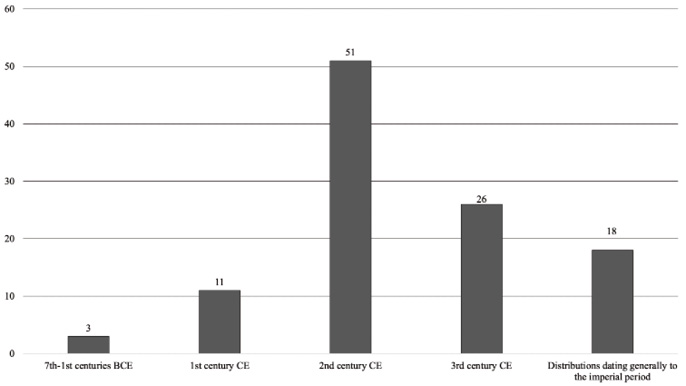

The chronological distribution of individualised monetary distributions in the eastern Mediterranean over the longue-durée, from the beginning of coinage in the late 7th century BCE to the Roman imperial world of the 3rd century CE, presents steep contrasts (fig. 1): an arid scarcity before the 1st century CE makes way for an oasis-like abundance in the 2nd and 3rd centuries[6]. While this in part reflects significant changes in epigraphic habit under the Roman empire, with inscriptions being by far our main source of evidence for cash handouts, the steepness of the change suggests a genuine cultural development was underway. To understand its historical contingency, however, it is necessary firstly to elaborate on, and in part explain, the near-absence of cash handouts in the pre-imperial period.

Figure 1. Inscriptions recording euergetic cash handouts in the eastern Mediterranean, 7th century BCE-3rd century CE, based on the 109 inscriptions in the appendix.

Our first recorded instance of an individualised monetary distribution dates to the earliest period of the history of coinage: the last Lydian monarch Kroisos gave two gold staters (his gold kroisid coins) to each Delphian citizen in the mid-6th century, as part of gifts to Delphi for an oracle presaging his future success —mistakenly, it would turn out— against Persia[7]. He was likely exploiting the radical new power of coinage as a means of defining value and gift in unprecedentedly individualised ways, extending its use beyond its origins in military pay in the late 7th century[8]. Innovative as it may have been, however, the notion of personalised distribution of coin as form of civic benefaction seems to have died with the Lydian kingdom – nothing of the sort is attested under succeeding Achaimenid kings or satraps, or even between the elite and non-elite of Greek poleis, as these came into contact with coinage from the 6th century onwards. Communal distributions in the archaic period, such as at feasts honouring victorious athletes, were distributions of sacrificial meat and gifts, but not of coin[9]. At early 5th-century Athens, famously, Kimon made the fruits of his house and gardens publicly available to the inhabitants of his deme (and possibly of the city more generally), but conducted no distribution of coined money[10]. The pattern continues throughout the 5th and 4th centuries at Athens, where our evidence is concentrated. The banquets organised by the elite, whether at local festivals through the liturgy of the hestiasis, or on the international stage, are known only to have involved distributions of sacrificial meat or grain[11]. This is true also for personalised distributions conducted by the state at communal events, as in a decree of 335/334 on the organisation of the Lesser Panathenaia[12]. Of course, the existence of coinage over this period meant that monetary distributions to individuals did become a possibility, and at Athens we find distributions of the proceeds of silver mining at Laurion in the early 5th century[13], and the establishment of pay for jurors and assembly-goers, and of the theoric fund[14]. Crucially, however, these were not distributions of an overtly euergetic character, and were organised by the state, not private individuals. The dominance of Athenian democratic ideology, in empowering the demos by allowing it to act as a benefactor to itself, may have both completed the logic inherent in coinage, as money whose authority was founded in the collective will of the community, and stifled the ambitions of private individuals of distributing coinage as a form of largesse[15].

Our evidence for public individualised distributions expands beyond Athens in the Hellenistic period, as the epigraphic habit became entrenched at communities across the Aegean and western Anatolia from the late 4th century onwards. Even so, the trends are largely the same as those found earlier. Distributions were mainly of commodities, and were mainly conducted by the state, not individuals, and even where euergetic distributions are attested, these only involved commodities, not coinage. For instance, the 3rd-century grain law at Samos outlines, as well as provisions for a grain-fund, a monthly distribution of this grain to the civic tribes[16]. Elsewhere, such distributions of grain[17], but also of sacrificial meat, were made on special communal occasions by civic governments and their representative magistrates: thus, several archons at Kos held a reception-feast for their fellow tribesmen, and the epimeletai of the Eleusinian mysteries at Athens distributed meat to the council[18]. Private individuals moreover played increasingly greater roles in the financing and running of communal sacrifices and banquets[19]. At late 3rd-century Eresos, the gymnasiarch Aglanor conducted feasts for the whole citizen body in honouring Ptolemy III, and later also spent much of his own money towards shields, races, and distributions of sacrificial meat for the youth of the gymnasium[20]. An increasingly large range of social groups was included at such sacrificial events and feasts[21]. Aglanor entertained the «whole demos» at the Ptolemaia (πανδᾶμι)[22]; at Arkesine on Amorgos, a series of archons who organised the festival of Athena Itonia in the 3rd and 2nd centuries distributed meat not only to citizens, but also the free non-citizen population, and resident foreigners[23]. The endowment set up by a Kritolaos for ritual feasting in memory of his son Aleximachos even included Romans and their sons[24]. Over the late 2nd to late 1st centuries, indeed, a culture of competitive inclusivity seems to have gripped the civic elite of the Aegean basin, as communal feasts at Priene, Kolophon, Kyme, and Pagai, among others, increasingly featured foreigners, paroikoi, freedmen and even women, children, and slaves, alongside citizens[25]. Moreover, products of ever more unusual quality were also distributed, beyond sacrificial meat alone, with some providing sweet-wine, at ceremonies of glykismos[26], and even types of porridge[27]. Feasts were also held at occasions outside the regular run of civic religious events alone: Soteles at Pagai held a feast at the consecration ceremony for his honorific statue, foreshadowing the distributions of coin that would take place at honorific statues in the imperial period, although Soteles seems to have done no more than hold a feast[28]. Gymnasia became scenes for public banquets from the 2nd century onwards[29], even as they witnessed evermore lavish distributions of training-oil, sometimes even of special varieties[30].

In all, this sizeable evidence for innovative forms of euergetic outlay at public feasts and distributions in the Hellenistic (and especially later Hellenistic) period says much about the changing shape of citizen bodies and ideas of citizenship in the face of growing Roman domination[31]. The striking and pertinent feature, however, is the absence of distributions of coined money comparable to those found in the imperial period. This was not for want of the possibility of thinking about distribution in monetary terms. Distribution had always involved monetary calculation, and especially in the classical and Hellenistic periods, when sacrificial feasts became major affairs involving large numbers of participants. Sacrificial animals were purchased according to certain earmarked sums of money, for instance[32], while some late Hellenistic decrees highlight the quantities of grain that were distributed to each recipient, reflecting exceptional acts worthy of honorific praise, but also the reality that minute calculation was involved[33]. Moreover, sacrificial meat was also distributed according to weight, as in the two minas’ worth of meat attendees received at feasts at Koressos, or the Euboian mina of beef handed out by a Prienian benefactor of the 1st century[34]: these minas were mina-weights, and not the commercial value of these sacrificial portions in minas, even if sacrificial meat was sometimes sold by portion[35].

Apart from a few doubtful cases, in fact, no civic notable before the imperial period is certainly attested conducting personalised distributions of coined money[36]. After Kroisos of Lydia, the only other case of an individualised cash handout in the pre-imperial period is also that of a king: Antiochos IV, who distributed a gold stater to each Greek inhabitant of Naukratis during his invasion of Egypt in 169 BCE[37]. Like Kroisos’ benefaction, however, this was probably a highly irregular act at an uncertain political moment, an isolated mention in Polybios otherwise unparalleled in the copious epigraphic record. It was more typical for royal power to work through to civic institutions: when queen Laodike set up a fund for dowries at Iasos, she only donated grain, leaving the prerogative of monetising and distributing that grain to the city itself[38]. Elsewhere, distributions of coined money were conducted only by civic governments, through institutions like assembly pay[39], and at public ceremonial events. At Bargylia (late 2nd century BCE, 100-drachma sums were given to various civic magistrates and groups for rearing sacrificial animals for Artemis Kindyas[40], while at Lampsakos seven drachmas were given to each citizen for sacrifices to Asklepios, and a sum of obols in lieu of a grain handout (2nd century BCE)[41]. If anything like a common thread is to be observed across the very scant evidence for cash handouts in the pre-imperial period, then, it would be that such activity could only be conceived, where it took place at all, by the state-entities who minted coinage, these being kings, like Kroisos, Antiochos IV, and civic governments, like Athens, Bargylia and Lampsakos. Where coinage —and especially precious-metal coinage in which large state expenditure was typically made— strongly remained the preserve of state authority, it may have been difficult for civic notables to engage in personalised distribution of coinage themselves: this is a point we will return to later on (section 3).

The weakening of royal and civic power in the face of Roman expansion, especially in the crucible of the 1st century BCE, may have laid the seeds of change. A hint may perhaps be found in an honorific inscription from Pinara, dated by Kalinka and Larsen to the early to mid-1st century BCE largely on the basis of letter-forms[42]. Among other benefactions, the honorand of the text distributed 5,000 drachmas to the associations of the xenokritai, and an unknown sum to the councillors, electoral magistrates, and office-holders of the Lykian koinon[43]. It is unclear whether these distributions were made to these groups as a whole, or to individual recipients, but the possibility remains that these represent some of the earliest individualised monetary distributions conducted by a local notable. The presumptive context would be the financial crises following the Mithridatic wars[44], which may have allowed for unusual forms of generosity. The dating of the inscription, however, is not entirely secure, and may well also belong in the 1st century CE or later, while in any case the fact that none of the other better documented civic benefactors of the late 2nd-1st centuries in Greece and Asia Minor seems to have done the same would mean that the Pinaran benefactor would have been very much an outlier[45].

In the end, the earliest secure case of an euergetic cash handout initiated by a citizen benefactor leads us no further back than the early 1st century CE, in the beneficent act of a couple at Lagina near Stratonikeia in Karia, Chrysaor and Panphile[46]:

[Χρ]υσάωρ Μεναλάου τοῦ Φιλίππου Ἱε(ροκωμήτης) | ὁ ἱερεὺς τῆς Ἑκά[τ]ης, καὶ Πανφίλη Παιωνίου Κω(ραιῒς) ἡ ἱέρηα, ἐπηνγε[ί]λαντο καὶ ἔδωκ[αν] | ἐν τῶι τῆς ἱερατ[εί]ας χρόνωι, εἰς τὰς ὑπὲρ τοῦ Σεβαστοῦ οἴκου καὶ ὑπὲρ τῆς Ἑκάτ[ης] | θυσ<ί>ας, τῶν μὲν π[ο]λειτῶν ἑκάστωι ἀνὰ δραχμὰς δέκα καὶ βουλευταῖς χʹ ἀνὰ δ[ραχμ]ὰς ἕξ· | τ̣[οῖ]ς δὲ ἄλλοις ἔ[τι] τοῖς κατοικοῦσιν τὴν πόλιν καὶ τὴν χώραν ἀνὰ δραχμὰς [πέντε?].

Chrysaor son of Menelaos, son of Philippos, of Hierakome, the priest of Hekate, and Panphile daughter of Paionios, of Koraze, the priestess (of Hekate), promised and gave, in the period of their priesthood, 10 drachmas to each citizen, six drachmas (more) to the 600 councillors, and furthermore to each of the other inhabitants of the city and countryside [five?] drachmas, towards the sacrifices for the house of Augustus, and Hekate.

The father of Chrysaor may be identified with a Menelaos attested as a priest in the time of Augustus[47]; which would place Chrysaor in the early to mid-1st century CE. The use of the expression «the house of Augustus» would also argue for this dating, with other examples of this phrase confined to the 1st century CE[48]. Over the 1st century, further instances of monetary distribution crop up at Akraiphia, Beroia, Smyrna, Iasos, Ephesos, Miletos, Aphrodisias, Akmoneia, and Patara[49]. Notably, some of these were conducted as distribution-events in their own right, where the specific memory of the benefactor was commemorated, and not as part of a public festival or communal event: for example, the distributions of G. Stertinius Orpex and his daughter Marina at Ephesos (of Neronian date) were made before their honorific statues[50], while the endowment of T. Flavius Praxias at Akmoneia stipulated an annual distribution to the councillors at his tomb[51]. By the early 2nd century, it had become customary in Bithynia-Pontus to give one or two denarii to members of the council and civic population at coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, when entering office, or at the dedication of public works: as Pliny complained to Trajan, these διανομαί were acts of excessive gift-giving that exceeded the bounds of gift-exchange between personal acquaintances[52]. Derisive attitudes like these, also articulated in various snippets in Plutarch and Lucian over the 2nd century, did little, however, to halt the trend[53]. From the late 1st century onwards public cash handouts are also attested in the western provinces on a large scale, making it an empire-wide phenomenon[54]. In the east, they more than triple in number over the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE (fig. 1). An age of numismatic euergetism was well and truly underway.

2. Augustan convergence and the imperial example

Individualised public distributions conducted by local notables in the classical and Hellenistic periods were almost invariably distributions of commodities, and cash handouts in the form of coined money were virtually non-existent, except for state initiatives by civic governments, or unusual acts of largesse by kings. Nonetheless, such cash handouts are increasingly attested from the early 1st century CE, and as distributions organised by local notables themselves. Why, then, did they become significant as a cultural practice only at the chronological turn of the 1st centuries BCE and CE, and not earlier?

As is well known, but perhaps under-appreciated, this was also a time when cash handouts were increasingly practised as a form of largesse at Rome itself. Julius Caesar had been the first to distribute congiaria (traditionally a handout of wine and oil) in cash, donating 400 sestertii to members of the plebs Romana in 46 BCE; this was followed by Augustus, who listed his monetary donations of 44, 29, 24, 12/11, 5, and 2 BCE in chapter 15 of the Res Gestae[55]. The successors of Augustus then continued to hold public monetary distributions, so that the practice became established as an imperial monopoly[56]. It is difficult to imagine that reports of these imperial cash distributions at Rome fell fully on deaf ears among the provincial elite of the Greek east. There is in fact some basis for believing that they did not, as the existence of inscribed copies of Augustus’ Res Gestae at Ankyra, Pisidian Antioch, and Apollonia in Galatia would invite us to suggest. The copy at Ankyra, for one, was cut at the same time as that of a list of the priests of the Galatian imperial cult on the left anta of the temple’s façade, suggesting that Augustus’ deeds, including the so-called «Appendix» at the end, which detailed building works and expenses towards spectacles and provincial cities, were meant to inspire the future euergetic actions of the priestly elite[57]. The Greek version was inscribed at eye-level, and even translated the monetary sums of chapter 15, which details Augustus’ congiaria distributions, into denarii, unlike the sestertii of the Latin —the denarius was the main unit of account by this point (as will be seen later), and these sums were clearly meant to be understood and taken seriously by local audiences[58].

Apart from this bona fide case of the local elite assimilating a record of imperial cash handouts, it has also been argued that the euergetic behaviour and self-fashioning of local notables, at least in Achaia, in the revival of local cults and customs, and architectural building at Athens, Sparta, and the Peloponnese, was shaped by Roman ideals and notions of «old Greece» promoted by Augustus and his court[59]. However exactly this process was replicated in Macedonia, the Aegean, and Asia Minor, the basic premise that imperial ideology could shape, whether consciously or subconsciously, aspects of the comportment and outlook of the civic elite is one that should be taken seriously. With cash handouts, it is significant that several of the earliest cases in the 1st century CE explicitly associated their distributions with honorific homage to the emperor – Chrysaor and Panphile did so to sponsor individual sacrifices to the imperial house, Potens of Iasos and Licinius at Xanthos made cash gifts on imperial birthdays, while Aristokles Molossos at Aphrodisias was a priest of the imperial cult[60]. Furthermore, in acting together as a married couple, Chrysaor and Panphile may have been enacting ideals of marital concord, and the role of women as public agents, that were increasingly exemplified by the imperial family: their presentation as a couple is largely unparalleled in earlier commemorative inscriptions for priests at Lagina or Panamara, which only record the priest alone[61].

The role of the local elite as conduits for the influence of imperial practice would be entirely unsurprising, as with other types of Romanising behaviour in the eastern Mediterranean (e.g. the spread of Roman citizenship, the use of Latin, or the growing popularity of bathing culture), for it was they who maintained the imperial cult, and served as ambassadors before Roman authorities. Another factor, however, was the communities of resident Romans in Greece and Asia Minor, many no doubt closely attuned to, and perhaps even personally beneficiaries, of practices like cash-distributions by the princeps. For instance, the prytanis Kleanax at Kyme (2 BCE-2 CE), who invited Romans to his feasts and distributions on a number of occasions, also carried out a «casting-out» (διαρρίφα) ceremony[62] —a ritual whose precise nature is unclear, but which may have involved the throwing of objects of largesse, perhaps in emulation of imperial distributions at Rome[63]. Interestingly, a similar casting-out (ῥίμματα) was conducted by Epaminondas of Akraiphia in the mid-1st century CE[64]. Moreover, some of the earliest benefactors, also of the same period, conducting cash handouts were of Italianate background —Potens of Iasos, or T. Peducaeus Canax and G. Stertinius Orpex of Ephesos[65]. Potens’ distribution of 25 denarii to councillors at a banquet (τῶι τρικλείνωι) almost certainly recreated the sportulae handed out at private feasts held by the Roman elite, while the distinction made in the distributions of Praxias at Akmoneia between those who were present (παρόντες), and standing, and the councillors who reclined to dine (κατακλεινόμενοι) in Roman style[66], likely corresponds to that between the praesentes and recumbentes found in later public sportulae in the western provinces[67]. These examples from Iasos and Akmoneia, however, are earlier in date, and may represent something like cultural over-compensation among the Italianate diaspora in Asia resulting from their relative distance from the imperial centre[68]. The mercantile background of many Italian immigrants may also have meant most held wealth primarily in cash, and not land, potentially making it easier for them to bridge the conceptual gulf between the acquisition and possession and monetised wealth, and its distribution through public benefaction.

The possibility that the cash handouts of Caesar, Augustus and their successors influenced local euergetic practice hints at the potential importance of role-models at the imperial level. In turn, this would explain the absence of cash handouts in earlier centuries. The Achaimenids never indulged in them, and the Hellenistic kings, for all the forms of generosity and gift-giving in which they engaged, almost never made individualised cash distributions —the example of Antiochos IV at Naukratis is anomalous, amid an extensive record of kings making gifts of commodities and money to whole communities, and leaving the further administration of these gifts and dissemination of their monetary proceeds to civic governments (as with Laodike’s gift to Iasos)[69]. Significantly, the gifts attested at royal feasts and processions never assumed the form of coinage[70]. The major Hellenistic monarchies never developed the sort of close-knit euergetic relations with the populaces of their capital cities that the leading generals of the Republic, and then the Roman emperors, would entertain at Rome: to the extent that the euergetic comportment of the civic elite were shaped by imperial exemplars, such exemplars existed in the early empire, but not before it.

In handing out coin, then, civic leaders like Chrysaor and Panphile were expressing their ideological affinity with forms of authority associated with the emperor, in his guise of benefactor. In doing so they also engaged with other types of authority —not least that of civic governments, which had long had oversight of the minting of coinage[71]. Donations of monetary sums as benefactions had been acceptable in the Hellenistic period, as long as these were gifts to the city, which notionally exercised sovereign oversight over coined monetary supply; individualised distributions of coinage by benefactors, however, may have posed a challenge to this prerogative, in presenting the negative optics of wealthy individuals issuing coinage themselves. That coinage did become prevalent as a medium of euergetic distribution would therefore suggest circumstances where civic authority over the production of coinage was less secure than before, even as demand for coinage seems to have remained high. This, indeed, is the picture that emerges when one sets the epigraphic evidence for cash handouts within the wider background of contemporaneous trends in monetary history in Greece and Anatolia, and the intersection of these trends with the intensifying fiscal demands of the Roman state, as the final section will now do.

3. Roman silver coinage and fiscal demands

The emergence of coinage as a medium of euergetic handouts was a change in forms and habit; it was not necessarily a sign that euergetic exchange had become more «monetised» or crudely transactional in character. Coinage, after all, had long been a part of the interchange between benefaction and honour in polis communities, in the sheer act of benefactors making gift-payments to their communities, even if not actually distributing coin as a benefaction in itself in the pre-imperial era; it moreover remained only one of a wider repertoire of commodities (e.g. grain, wine, and oil) used in distributions in the imperial period[72]. Coinage certainly offered calculability, and the possibility of defining distinctions of social status with a precision unavailable to non-monetary commodities —the privileging of members of the council or gerousia, for instance (as with Antaios of Syros and Chrysaor and Panphile at Stratonikeia)[73]. However, these hierarchising processes were already underway in the late Hellenistic period when coinage was not a major part of public distributions, so that it cannot be regarded as intrinsic or essential to them. What the appearance of cash handouts should simply be understood to reflect is pervasive monetisation: circumstances where coinage was more ubiquitous, so that it could be readily seized on as a medium in public distributions, where commodities had previously dominated. The broader economic phenomenon this may represent is simply larger cash-flow in the early Roman empire, with cash handouts being but a glint in the wider floodlights of monetary history[74]. To gain a more fine-grained picture, we may also consider the sorts of coins that were actually distributed at cash handouts. This is not difficult to know, as inscribed records of distributions over the 1st to 3rd centuries CE often mention the currencies in which they were made (figs. 2-3)[75].

Figure 2. Instances of currencies in inscriptions recording euergetic cash handouts dateable to the 1st, 2nd or 3rd centuries CE, based on nos. 4-7, 9, 11-12, 14-15, 18-20, 22-24, 26-28, 30-35, 38-44, 48-49, 51, 53-54, 56, 58-62, 64-65, 67-69, 71-73, 76, 78, 83-85, 87, 89-91 in the appendix (59 inscriptions).

Figure 3. Instances of currencies in inscriptions recording euergetic cash handouts dated generally to the imperial period, based on nos. 92-93, 96-97, 99-100, 102, 104-105, 107-108 in the appendix (11 inscriptions).

The rarity of the obol and assarion is unsurprising, given the honorific context of the vast majority of these documents, as silver fractions and bronze currency only relate to small monetary amounts. The gold aureus is also rare, known from only one instance. On the other hand, most monetary sums, from the onset of monetary distributions in the 1st century CE, are given in silver denominations —the denarius, and also occasionally the drachma and «Attic» drachma[76]. It is likely this epigraphic record reflects the actual currencies that were used, and not merely units of account —silver fractions and bronze are rare, as it would have been impractical to distribute such large sums in small change alone[77], while conversely individual handouts were rarely large enough to require the use of the aureus (worth 25 denarii)[78]. The dominance of silver denominations also suggests that the emergence of cash handouts was related to developments in the history of silver currency.

Indeed, a major transition is detectable here over the 1st century BCE, with communities in Balkan Greece and Asia Minor shifting irreversibly to the use of the denarius and Roman monetary standards, and phasing out the civic minting of silver coinage. This is especially clear in Greece and Macedonia. In Thessaly, the silver staters of the Thessalian koinon, first struck in 168, extend down to the 40s BCE; Augustus’ diorthoma of 27 BCE, regulating the value of the Thessalian stater at 1.5 denarii, shows that the latter had become the main currency by that point[79]. A similar lifespan may be suggested for the post-146 coinage of the Achaian koinon and other Peloponnesian cities, where several tetrobol series attest to Roman influence[80], while Athens’ New Style tetradrachms, which probably financed Roman military operations in the 1st century BCE, came to an end around 40 BCE[81]. An inscription recording an eight-obol tax at Messene shows that the denarius and its weight-standard had replaced the Attic drachm in southern Greece as the main unit of account by this point[82]. In Macedonia, the prevailing silver coinages from provincialisation in 148 to the mid-1st century BCE (Macedonian merides issues, Athenian and Thasian tetradrachms, drachms of Apollonia and Dyrrachion, the «Aesillas» coinage) were thereafter unmistakeably replaced by denarii, which dominate hoards from c. 48 BCE to the early imperial period[83]. By the early 1st century CE, no civic mints in the provinces of Achaia and Macedonia actively produced silver coinage anymore.

In Asia Minor the situation is more complex, but shows a similar trend. The cistophoric coinage of the Attalids was maintained as the main silver currency in Asia after provincialisation in 129, —mints actually increased in number up to the mid-1st century— and indeed enjoyed a status as a surrogate Roman currency until the 2nd century CE[84]. At the same time, the number of cities that had struck silver coinage of their own throughout the 2nd century gradually decreased from 129 onwards, as the privilege of such minting was increasingly tied to political loyalty to Rome —a reality that became stark during the Mithridatic and then Civil Wars[85]. The large outputs of cistophori by Antony and Octavian in the 30s and 20s BCE, followed by issues of denarii in the 10s, contributed to flooding out local civic silver[86]. Alongside these changes in production, the weight-standards of civic coinage were gradually aligned with those of the denarius and quinarius (a half-denarius) over the 80s to 40s, while from the mid-1st century the cistophoric drachm was itself increasingly tariffed at three-quarters of a denarius[87]. By the early 1st century CE, only the Lykian koinon and five cities in Asia (Chios, Rhodes, Stratonikeia, Mylasa, Tabai) still minted local silver types, and, even then, only on the standard of the denarius-aligned cistophoric drachm (Rhodes, Chios) or the denarius (Stratonikeia, Mylasa, Tabai, Lykia)[88]. Of these coinages, only the Lykian koinon’s would last beyond the 1st century CE.

The unfolding of these processes was complex, and likely involved the intertwining of imperial and local decision-making[89]. The result was clear, however —the undeniable dominance of Roman standards for silver production by the late 1st century BCE, with the denarius supplanting civic silver coinage in Achaia and Macedonia, while in Asia the Romanised cistophorus became the main provincial silver currency alongside the denarius, whose weight-standard it followed. Except for a handful of privileged communities in Asia Minor, independent civic minting of silver coinage came to an end. The first recorded cases of cash handouts, then, were carried out in a monetary landscape dominated by Roman silver coinage, where presumably provincial officials, not civic authorities, had oversight of silver minting. It is difficult to imagine that this state of affairs had no effect on local attitudes towards silver coinage. Where it had been a medium for expressing and communicating a community’s sense of political identity in the classical and Hellenistic periods, and its minting a particularly cherished prerogative of civic authorities, this was no longer true under Roman imperial monarchy; bronze coinage would now assume this mantle. In these circumstances, the conceptual link between silver coinage and civic control over its minting, alongside its attendant symbolic resonances for communal self-identity, may have gradually diminished. So long as this link had remained strong, the physical distribution of silver coinage would have been confined to the official duties of mint-magistrates; as these associations weakened, so might control over its distribution have shifted away from such magistrates alone, and moved into the hands of those among the elite capable of monetising their wealth on a large scale, some of whom gave out silver coins while holding other types of civic office, or no office at all. That is to say, the end of the civic minting of silver coinage created conditions that allowed for the acceptability of its ceremonious dissemination by local notables, and hence of cash handouts a form of civic benefaction, by the early 1st century CE.

Figure 4. RPC I 2778.1 (= Münzkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 18258514 (photographed by Bernhard Weisser https://ikmk.smb.museum/object?id=18266358), silver hemidrachm from Stratonikeia, obverse with a head of Hekate, with legend ΑΡΙΣΤΕΑΣ, and reverse with Nike and legend ΧΙΔΡΩΝ ΣΤΡΑ; 1.40g. https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/coins/1/2778

It is the case, however, that some cities where early cash handouts are attested also continued to strike their own silver coinage: Chrysaor and Panphile’s Stratonikeia is precisely a case in point. It is tempting to associate the drachmas they distributed with the rare Stratonikeian drachms and hemidrachms of the early 1st century CE, like the one with a head of Hekate obverse and standing Nike reverse (fig. 4)[90], and thus to characterise their distributions not as a sign of the weakening link between civic authorities and silver coinage, but rather as a reflection of Stratonikeian civic pride in their ongoing right to mint silver, the long-term result of the city’s privileged history of friendship with Rome since the Mithridatic wars[91]. Local responses to the changes in civic authority over silver coinage would have varied, in any case. More likely, however, the use of drachmas simply refers to a unit of account. For one, these Stratonikeian drachms were struck on the denarius standard, and were thus effectively Roman currency[92]. They were also a small production, mostly known from single specimens. This is similar to the contemporary coinage of Chios struck from the gift of Antiochos IV of Kommagene, unusual in being a civic silver coinage certainly originating in a benefaction (signed ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΥ ΔΩΡΟΝ), which was also a small production and comprised only a fraction of the original 15 talents of the donation[93]. Likewise, Stratonikeian drachms are unlikely to have made up the entirety of Chrysaor and Panphile’s distribution, which was probably supplemented by provincial silver currency in denarii or cistophoric drachms. The mention of drachmas at Stratonikeia therefore more probably represents the practical use of a unit of account equivalent to the denarius, and not necessarily any special feeling of pride in a civic silver coinage; the same is likely to be true for other sporadic references to drachmas in the epigraphic record of the imperial period[94].

Beyond the ideological impacts brought about by changes in the nature of minting authority in relation to silver coinage, however, the distributions of the Stratonikeian couple and others like them can also be set in productive tension against other impositions of the Roman state, and in particular its fiscal demands. In this sphere, also, the Augustan epoch marked a subtle but significant shift, in intensifying the penetration of the state at the local level, and increasing the need for coined money among local populations. In Asia, Julius Caesar had ended the regime of the publicani over the collection of the tithe, and transferred responsibility for the collection of fiscal dues to cities[95]. While publicani continued to exact tolls and customs-dues, and some direct taxes, the main administrative burden for tax-collection henceforth fell on civic governments and their elite citizens. Augustus systematised this process, by generalising census-taking across the provinces, and regularising exaction of direct tax, as the proportional levies (such as a tithe or an eighth) that had been collected by Republican publicani were increasingly substituted for fixed levies (based on the size of a landed property, for instance), which were defined in terms of taxes on property (tributum soli) and the poll-tax (tributum capitis)[96]. While the precise workings of these developments remain hazy, the overall impression is that the poll-tax became an increasingly intrusive and burdensome obligation, with civic benefactors in the Aegean area even praised for providing relief-payments and establishing foundations towards covering its impositions[97]. While absolute comparisons are impossible, the regularised and personalised imposition represented by the poll-tax of the imperial period may have marked an increase in scale and sophistication unmatched by the earlier Seleukid, Attalid or Antigonid monarchies, for whom we have comparably little evidence for poll-taxes[98], and certainly no similar indication (or at least in a manner that called for epigraphic preservation) that local benefactors faced comparable pressure to make donations that addressed fiscal obligations.

The fact that coinages in Greece and Asia Minor converged on Roman monetary standards at this time is not necessarily coincidental. Epigraphic testimonies for the poll-tax show that it was accounted for in silver currency (denarii and drachmas), suggesting it was paid in coins, and not just in kind —most likely the Roman silver currencies in Achaia and Macedonia (denarius), and Asia Minor (denarius and imperial cistophorus)[99]. The intensification and regularisation of direct taxation is likely to have increased the demand for coinage, and in turn facilitated the convergence on Roman monetary standards. Euergetic cash handouts may thus have gained traction as a form of benefaction because they partly served the need for coin among civic populations: indeed, the amounts attested in cash handouts across the imperial period, per capita, would not have been too far off those that were actually paid in poll-tax, to judge from amounts known from Egyptian tax-receipts[100]. In some cases, a monetary gift by a benefactor may well have contributed considerably to paying an individual’s tax burden, and especially so in cases of testamentary foundations that were set up for annually recurring distributions.

The ideological and theatrical aspect of handouts would also have been significant. The payment of tax in coin, after all, can be seen to mirror and pre-figure the phenomenon of monetary distribution —direct taxation demanded that individuals make payments of fixed sums of coins to the state, while cash handouts comprised the distribution of fixed sums of coins, as gifts, to these same individuals. The potential for burlesque was latent. That is to say, distributions of coinage might have evoked and even subversively satirised the act of paying tax, forming carnivalesque role-reversals where tax-payer became coin-recipient and the tax-collector a civic benefactor, and thereby afforded a psychological salve to the burden it represented[101]. Obviously, the inherently selective and hierarchical nature of distributions —in particular the favouritism openly accorded to councillors and other members of the elite— means that this mirroring quality may just as well have aggravated a sense of fiscal intrusiveness and inequality, as alleviated it. Moreover, it was the members of the local elite themselves who often held direct responsibility for advancing and collecting tax due to Roman authorities, as with the officials known as the dekaprotoi, and their distributions of coin may in this light have had a strongly ironic element[102]. How precisely those who conducted or participated in monetary distributions may have felt about what they were doing can only remain a matter of speculation, of course. The point here is rather that the pervasiveness of Roman taxation, and the rituals of paying coin to the Roman state that must have ensued and become prevalent, contributed to a cultural setting in which the euergetic distribution of coinage could be conceived as a practice —where, in effect, the local elite could deploy forms of action associated with the imperial order (apart from the example of imperial congiaria at Rome alone) in their contests for honorific distinction. We might give the final say to the benefactor Satyros of Tenos, who lived in the 1st-2nd centuries CE. Among his crowning achievements was an endowment of funds towards the payment of the ἐπικεφάλιον, the poll-tax. This was clearly regarded as being part of a broader program of monetary distribution, however, because the preceding lines of the same inscription honouring him listed the numerous cash handouts he had made over his public career[103]. Distributions of coin were thus conceptually associated with the payment of fiscal obligations to the Roman state; it is hard to believe Tenos was alone in this regard.

Conclusion

The public distribution of individualised gifts of coined money by the civic elite of the Aegean basin and Anatolia was a phenomenon of the Roman empire. In the classical and Hellenistic periods such distributions were infrequent, and anyhow conducted by civic governments, rarely by kings, and even when wealthy benefactors emerged in the later Hellenistic period public distributions were still mainly distributions of commodities, not coins. The emergence of cash handouts coincided with the onset of the principate and its related monetary and fiscal history. The example of cash distributions by the early imperial rulers at Rome, perhaps also transmitted through social groups like resident Romans, was imitated and disseminated by the civic elite. Secondly, broader changes in the production of silver coinage at this time, the specie in which cash handouts were primarily made, were influential. The fact that civic silver coinage largely came to an end by the early 1st century CE, and was superseded by the denarius, or other coinages based on Roman monetary standards like the cistophorus, may have contributed to weakening the conceptual association between civic authorities and silver coinage, allowing wealthy individuals to appear publicly as the distributors of precious-metal coins. These monetary developments were also likely related to increasingly extractive direct taxation practised by the early imperial Roman state, in the form of property- and poll-taxes payable in coin. Cash handouts may in this light have responded to a heightened need for cash among the non-elite, while potentially also serving simultaneously to normalise Roman taxation by casting it in the symbolic terms of civic euergetism and spectacle. In all, the conjuncture of these three aspects —the imperial example, changes in monetary history, and the intensification of Roman fiscal demands— created the conditions that allowed for the emergence and popularisation of cash handouts in Greece and Asia Minor.

These processes operated alongside the steepening social stratification within civic society that much scholarship has emphasised, and which monetary gifts facilitated; the point here is that the rise of cash handouts cannot only be seen as an «indigenous» development of the poleis, and must also be set within the broader frameworks embodied by the Roman state. The fact that they may have appeared earlier than in the western provinces, where they are only attested in serious numbers from the early 2nd century CE, may further suggest that it was the relative distance of the Hellenistic world, both geographically and culturally, that paradoxically allowed for more overt imitation of imperial practice, while the proximity of the municipal elite in Italy and Gaul to Rome invited greater circumspection. In other words, the emergence of euergetic distributions of coin exemplifies some of the dynamics galvanised by the confrontation between Rome and the cultural habits of its provinces.

Appendix: Euergetic cash handouts in the eastern Mediterranean, 7th century BCE to 3rd century CE

The following, on which figures 1 and 2 are based, presents a reference list for attestations of euergetic cash handouts carried out by individual benefactors, as gathered from an extensive but not exhaustive survey of the epigraphical corpora and scholarly literature (see footnote 2 and also under «Verteilungen» in the index to Quaß 1993). It is likely to be representative of chronological trends, even if omissions will doubtless be found; handouts conducted by civic authorities (e.g. I.Thespiai 37 ll. 16-20) are not included. Dates for inscriptions follow those of published editions.

|

No. |

Source |

Community |

Date |

Name/s of benefactor/s |

Monetary amount/s and recipients |

Currency/currencies specified |

|

1 |

Hdt. 1.54, Plut. Mor. 556f |

Delphi |

Mid-6th century BCE |

Kroisos |

2 gold staters or 4 minas to each citizen of Delphi |

Stater, mina |

|

2 |

Polyb. 28.20.11 |

Naukratis |

169 BCE |

Antiochos IV of Syria |

A gold stater to each Greek citizen |

Stater |

|

3 |

TAM II 508 ll. 21-23 |

Pinara |

Early to mid-1st century BCE (?) |

Unknown |

5,000 drachmas to the associations of the xenokritai, and an unknown sum each (?) to the councillors, electoral magistrates, and office-holders of the Lykian koinon |

Unknown |

|

4 |

I.Stratonikeia 662 A ll. 4-5 |

Stratonikeia |

Early 1st century CE |

Chrysaor and Panphile |

10 drachmas to each citizen, 6 drachmas in addition to the councillors, and an unknown amount of drachmas to other inhabitants of the city |

Drachma |

|

5 |

IG VII 2712 ll. 78-82 |

Akraiphia |

Mid-1st century CE |

Epaminondas |

11 denarii each to the magistrates, 6 denarii to the other inhabitants in lieu of a public meal |

Denarius |

|

6 |

SEG 43.717 ll. 19-21 |

Iasos |

Mid-1st century CE |

Potens |

25 denarii each to the councillors on Claudius’ birthday |

Denarius |

|

7 |

I.Aphrodisias 12.803 ll. 22-32, 35-42 |

Aphrodisias |

Mid-1st century CE |

Aristokles Molossos |

Donated estates towards monetary distributions (argyrikai diadoseis) to the citizens on specified days |

Denarius (most likely, from ll. 56-62) |

|

8 |

I.Ephesos 702 ll. 11-12 |

Ephesos |

54-68 CE (cf. SEG 39.1179) |

T. Peducaeus Canax |

Donated unspecified monetary amounts (kathieroseis argyrion) to the council and gerousia |

Unknown |

|

9 |

I.Ephesos 4123 ll. 9-17 |

Ephesos |

54-68 CE |

G. Stertinius Orpex and Marina |

Donated 5,000 denarii for distributions (dianomai) to the councillors, 2,500 denarii for distributions of 2 denarii each to the gerousiastai, and 1,500 denarii for distributions of 3 denarii each to select individuals towards a feast |

Denarius, drachma |

|

10 |

I.Didyma 264 ll. 14-15 |

Miletos |

50-100 CE |

Iason |

Conducted unspecified distributions (dianomai) for the council and citizens |

Unknown |

|

11 |

IGR IV 661 ll. 1-3, 21-22 |

Akmoneia |

85 CE |

T. Flavius Praxias |

Conducted a distribution (dianome) to the freedmen; another unspecified distribution (dianome) to the councillors |

Denarius (most likely, from l. 8) |

|

12 |

SEG 65.1483 ll. 8-18 |

Patara |

83-96 CE |

Licinius |

5 denarii to each Lykian, and 3 denarii each to the Tloans, Xanthians, Myrans, Patarans on imperial birthdays |

Denarius |

|

13 |

I.Beroia 117 ll. 19-21 |

Beroia |

Late 1st century CE |

Q. Popillius Python |

Mention of unspecified distributions (diadomata) to the people |

Unknown |

|

14 |

I.Smyrna 709 ll. 16-17 |

Smyrna |

1st century CE |

Claudius Karteromachos |

5 denarii to each citizen or councillor (?) |

Denarius |

|

15 |

Philostr. V S 549 |

Athens |

138/139 CE |

Ti. Claudius Atticus Herodes |

Donated money for an annual distribution of a mina to each Athenian citizen |

Mina |

|

16 |

Luc. De mort. Peregr. 15 |

Parion |

Early 2nd century CE |

Peregrinus |

Donated property towards distributions (dianomai) to the people |

Unknown |

|

17 |

TAM II 539 ll. 7-8 |

Arsada |

1st-2nd centuries CE (cf. Kılıç Aslan 2023, 228) |

Symbras |

Unspecified monetary distribution at a feast |

Unknown |

|

18 |

I.Lampsakos 12 ll. 7-8 |

Lampsakos |

1st-2nd centuries CE |

Kyros |

1,000 Attic drachmas to the gerousia |

Attic drachma |

|

19 |

IG XII.5 946 ll. 5-18 |

Tenos |

1st-2nd centuries CE |

Satyros |

5,000 denarii for annual distributions of 1 denarius to each male citizen, and two other donations of 10,000 and 6,000 denarii for annual distributions |

Denarius |

|

20 |

I.Stratonikeia 172 ll. 12-13 |

Stratonikeia |

Late 1st-early 2nd centuries CE |

Ti. Claudius Lainas |

2,400 denarii to the council for distributions |

Denarius |

|

21 |

I.Sardis 43 ll. 2-4 |

Sardeis |

1st-early 2nd centuries CE |

Ti. Claudius Silanus |

Bequeathed an unspecified amount for an annual distribution (dianome) |

Unknown |

|

22 |

IGR III 493 ll. 13-15 |

Oinoanda |

Early 2nd century CE |

G. Licinnius Marcius Thoantianus Fronto |

10 denarii to each citizen |

Denarius |

|

23 |

I.Ephesos 2061 II ll. 11-12 |

Ephesos |

103-116 CE |

Ti. Flavius Montanus |

Provided 3 denarii to each citizen for lunch |

Denarius |

|

24 |

I.Ephesos 27 ll. 220-352, 485-553 |

Ephesos |

104 CE |

G. Vibius Salutaris |

Distributions ranging from 4.5 assaria to 30 denarii for a range of individuals and civic and temple officials at Ephesos; cf. Rogers 1991, 41-72 |

Denarius, assarion |

|

25 |

IG IV 602 ll. 10-11 |

Argos |

116-117 CE |

Ti. Claudius Tertius Flavianus |

Mention of unspecified monetary distributions (dianomai) |

Unknown |

|

26 |

I.Ephesos 712B ll. 16-18 |

Ephesos |

117-138 CE |

Publius Quintilius Valens Varius |

2 denarii each to 1,000 citizens selected by lot |

Denarius |

|

27 |

SEG 63.1342 ll. 9-11 |

Patara |

117-138 CE |

Claudia Anassa |

Donation for an annual distribution of 6.5 denarii to each citizen |

Denarius |

|

28 |

SEG 38.1462B ll. 26-27 |

Oinoanda |

125-126 CE |

G. Julius Demosthenes |

3 denarii each to 500 sitometroumenoi selected by lot, and donation of 300 denarii to be distributed among the other citizens and paroikoi |

Denarius |

|

29 |

I.Didyma 254 ll. 4-6 |

Miletos |

130-138 CE |

L. Apidianus Kallikrates |

Unspecified monetary distributions (dianomai) to the council and all citizens |

Unknown |

|

30 |

TAM II 578/579 (a copy of 578) ll. 28-30 |

Tlos |

136 CE |

Opramoas |

1 denarius to each sitometroumenos |

Denarius |

|

31 |

I.Ephesos 618 ll. 18-20 |

Ephesos |

140 CE |

M. Ulpius Aristokrates |

Mention of a distribution (dianome) to the gerousia out of a fund of 100,000 denarii |

Denarius |

|

32 |

SEG 27.938 ll. 8-11 |

Tlos |

150 CE |

Lalla |

1 denarius to each sitometroumenos |

Denarius |

|

33 |

I.Didyma 279 B ll. 3-10 |

Miletos |

100-150 CE |

M. Flavianus Phileas |

Numerous distributions for women, maidens, councillors and the kosmoi, and distributed 2 denarii to each citizen |

Denarius |

|

34 |

I.Stratonikeia 237 ll. 13-15 |

Stratonikeia |

100-150 CE |

M. Ulpius Ariston and Aelius Tryphaina Drakontis |

3 denarii each to the councillors and leading members of the gerousia |

Denarius |

|

35 |

I.Ephesos 690 ll. 21-25 |

Ephesos |

117-161 CE |

G. Julius Pontianus |

1 denarius each to 124 councillors and priests |

Denarius |

|

36 |

I.Tralleis und Nysa II 440 ll. 18-23 |

Nysa |

138-161 CE |

T. Aelius Alkibiades |

Donated horse-pastures for annual monetary distributions on Hadrian’s birthday |

Unknown |

|

37 |

I.Tralleis und Nysa II 441 ll. 22-29 |

Nysa |

138-161 CE |

T. Aelius Alkibiades |

Distributed unspecified amounts to each citizen, by tribe and symmoria, at the assembly and council |

Unknown |

|

38 |

IG XII.5 659 ll. 11-20 |

Syros |

138-161 CE |

Aristagoras |

3 denarii each to the gerousiastai, and 8 assaria to women and children on the first day of his stephanephoria; 7 denarii each to the stephanephoroi, 1 denarius to all citizens, on the second day of his stephanephoria |

Denarius, assarion |

|

39 |

SEG 63.1402 ll. 15-18 |

Seleukeia-on-the-Kalykadnos |

142-161 CE |

Dionysodoros |

11 obols each to councillors and magistrates, distributed 6,200 denarii (?) to the people for distributions, and 12 obols each to members of the gerousia |

Denarius, obol |

|

40 |

I.Stratonikeia 527 ll. 6-7 |

Stratonikeia |

Mid-2nd century CE |

Herakleitos and Tatarion Polynike |

3 drachmas (?) each to citizens, 2 drachmas (?) to Romans, foreigners, paroikoi |

Drachma |

|

41 |

I.Stratonikeia 1428 ll. 12-14 |

Stratonikeia |

Mid-2nd century CE |

Herakleitos and Tatarion Polynike |

2 drachmas each to citizens and other inhabitants of the city |

Drachma |

|

42 |

F.Xanthos VII 67 ll. 21-22, 37-40 |

Xanthos |

After 152 CE |

Opramoas (?) |

10 drachmas to each councillor in Lykia, 1 aureus each to the councillors, gerousiastai and sitometroumenoi of Xanthos, and 10 drachmas each to other citizens and metoikoi |

Drachma, aureus |

|

43 |

I.Histria 57 ll. 24-29 |

Histria |

150-200 CE |

Aba |

2 denarii each to the councillors, gerousiastai, the Tauriastai, doctors, teachers, and private individuals named by Aba |

Denarius |

|

44 |

Milet VI.2 945 ll. 1-11 |

Miletos |

170-200 CE |

Charis |

Donated 3,000 denarii to the council for annual distributions on a specified date of 12 denarii to each councillor |

Denarius |

|

45 |

I.Prusias ad Hypium 17 ll. 18-21 |

Prousias-under-Hypios |

Late 2nd century CE |

T. Ulpius Aelianus Papianus |

Held two distributions (nomai) for those registered as citizens and those inhabiting the fields |

Unknown |

|

46 |

I.Ephesos 26 ll. 17-18 |

Ephesos |

180-192 CE |

Nikomedes |

Mention of distributions (dianomai) to the citizens |

Unknown |

|

47 |

I.Cret. IV 300 B ll. 1-13 |

Gortyn |

180-182 CE |

T. Flavius Xenion |

Unspecified monetary donations on seven imperial birthdays and the date of Rome’s foundation |

Unknown |

|

48 |

IG XII.5 663 ll. 14-27 |

Syros |

183 CE |

Antaios |

5 denarii each to the gerousiastai in lieu of a basket-lunch, 8 assaria to women, and 4 assaria to children on the first day of his stephanephoria; 1 denarius each to the gerousiastai, 1 denarius to citizens, and 8 assaria to free persons and children, on the second day of his stephanephoria |

Denarius, assarion |

|

49 |

IG XII.5 664 ll. 10-15 |

Syros |

193-198 CE |

Modestus |

Unknown amount of denarii in lieu of a basket-lunch, and 8 assaria and wine to free women and girls |

Denarius, assarion |

|

50 |

TAM V.2 983 ll. 6-7 |

Thyateira |

c. 200 CE |

Unknown |

Unspecified distributions (dianomai) |

Unknown |

|

51 |

MAMA III 50 ll. 10-18 |

Dösene, Cilicia |

2nd century CE |

Angklous |

Donated 1,200 drachmas towards annual distributions to every man during the pannychis |

Drachma |

|

52 |

I.Magnesia 179 ll. 28-30 |

Magnesia |

2nd century CE |

Son of Apollonios |

Unspecified distribution (dianome) to the council at the consecration ceremony for his honorific statue |

Unknown |

|

53 |

I.Didyma 111 ll. 1-8 |

Miletos |

2nd century CE |

Unknown |

Donated 1,000 denarii to Apollo and the council for distributions |

Denarius |

|

54 |

I.Didyma 269 ll. 6-11, 270 ll. 6-11 |

Miletos |

2nd century CE |

Ti. Claudius Marcianus Smaragdos |

1 denarius to each councillor, woman, virgin, and male citizen in lieu of a basket-lunch (cf. Robert, Hellenica XI-XII 479-480) |

Denarius |

|

55 |

I.Didyma 271 ll. 1-2 |

Miletos |

2nd century CE |

Ti. Claudius Marcianus Smaragdos |

Unspecified distribution (dianome) to the children |

Unknown |

|

56 |

TAM V.3 1457 ll. 8-18 |

Philadelphia |

2nd century CE |

Diogenes |

Donated 2,500 denarii and 1,500 denarii to the councillors and synedrion of the presbyteroi for annual distributions on his birthday |

Denarius |

|

57 |

I.Prusias ad Hypium 18 ll. 9-11, 19 ll. 10-12 |

Prousias-under-Hypios |

2nd century CE |

P. Domitius Julianus |

Distributed unspecified monetary amounts as gifts to the people |

Unknown |

|

58 |

IG XII.1 95 B ll. 3-6 |

Rhodes |

2nd century CE |

M. Claudius Caninius Severus |

12 denarii to each citizen, unknown amount to the therinoi (?), 24 denarii to an unknown group |

Denarius |

|

59 |

IGR III 800 ll. 5-12 |

Sillyon |

2nd century CE |

Megakles and Menodora |

20 denarii each to the councillors, 18 denarii to the geraiai and ekklesiastai, 2 denarii to the citizens, 1 denarius to the freedmen and paroikoi |

Denarius |

|

60 |

IGR III 801 ll. 14-22 |

Sillyon |

2nd century CE |

Menodora |

85 denarii each to the councillors, 80 denarii to the geraioi, 77 denarii to the ekklesiastai, 3 denarii to the wives of the ekklesiastai, 9 denarii to the citizens, 3 denarii to the vindictarii, freedmen and paroikoi |

Denarius |

|

61 |

IGR III 802 ll. 18-26 |

Sillyon |

2nd century CE |

Menodora |

85 denarii each to the councillors, 81 denarii to the geraioi, 75 denarii to the ekklesiastai, 3 denarii to the wives of the ekklesiastai, 4 denarii to the vindictarii and freedmen |

Denarius |

|

62 |

I.Stratonikeia 192 ll. 7-10 |

Stratonikeia |

2nd century CE |

Ti. Flavius [---] and Flavia Mamalon |

5 drachmas each to men and 3 drachmas to women at the Kamuria and Heraia festivals |

Drachma |

|

63 |

I.Stratonikeia 1028 ll. 18-21 |

Stratonikeia |

2nd century CE |

Hierokles |

Mention of a distribution (dianome) |

Unknown |

|

64 |

I.Stratonikeia 205 l. 37 |

Stratonikeia |

2nd century CE |

Ti. Flavius Iason and Aelia Statilia |

Distributed 10,000 denarii to the citizens |

Denarius |

|

65 |

IG XII.5 665 ll. 1-16 |

Syros |

2nd century CE |

Unknown |

6 denarii each to the gerousiastai in lieu of a basket-lunch, 8 assaria to women, and 4 assaria to children, on the first day of his stephanephoria; 1 denarius each to the gerousiastai, 1 denarius to citizens, and 8 assaria to free persons and children, on the second day of his stephanephoria |

Denarius, assarion |

|

66 |

I.Aphrodisias 1.161 ll. 2-10 |

Aphrodisias |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

Unknown |

Donated money towards annual distributions (kleroi) to the council and chrysophoroi by lot |

Unknown |

|

67 |

I.Aphrodisias 11.533 ll. 12-35 |

Aphrodisias |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

Aurelia Ammia Myrton and M. Aurelius Diogenes |

Donated 2,545 denarii and 1,500 towards distributions (kleroi) to the council |

Denarius |

|

68 |

I.Aphrodisias 12.317 ll. 9-12 |

Aphrodisias |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

L. Antonius Zosas |

Donated 3,000 denarii each to the council and gerousia for annual distributions (kleroi) |

Denarius |

|

69 |

I.Aphrodisias 12.534 ll. 21-28 |

Aphrodisias |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

Aurelia Ammia |

Donated 2,370 denarii for distributions (kleroi) to the council |

Denarius |

|

70 |

SEG 53.891 ll. 14-18 |

Oine |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

Unknown |

Mention of distribution of an unknown amount of denarii to the dekaprotoi (?) |

Unknown |

|

71 |

I.Stratonikeia 311 ll. 13-17, 25-31 |

Stratonikeia |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

M. Aurelius Arrianus and Aurelia Chotarion |

1 denarius to each woman in lieu of a dinner; distributed a further unknown amount to citizens and foreigners at feasts with triclinia |

Denarius |

|

72 |

IG XII.5 954 A ll. 2-5 |

Tenos |

2nd-3rd centuries CE |

Unknown |

8 denarii each to the councillors, and other unknown amounts to other groups |

Denarius |

|

73 |

I.Tralleis und Nysa I 66 ll. 7-9 |

Tralleis |

150-250 CE |

M. Aurelius Euarestos |

Donated 3,333 denarii towards annual distributions (nome) to the council on his birthday |

Denarius |

|

74 |

I.Ephesos 951 ll. 5-9 |

Ephesos |

Late 2nd-early 3rd centuries CE |

Aurelius Varanus |

Distributed 40,000 denarii (?) to the council, all the synedria, and the citizens |

Unknown |

|

75 |

TAM V.3 1475 ll. 2-9 |

Philadelphia |

Late 2nd-early 3rd centuries CE |

Cornelia |

Donated an estate for annual distributions (nemesthai) to the councillors on the birthday of her brother, at their statues |

Unknown |

|

76 |

TAM III.1 108 ll. 8-17 |

Termessos |

219-229 CE |

M. Aurelius Platonianus Otanes |

Donated 165,500 denarii towards perpetual distribution (nemesis) |

Denarius |

|

77 |

I.Selge 20 A ll. 1-3 |

Selge |

225-250 CE |

P. Plancius Magnianus Aelianus Arrius Perikles |

Mention of unspecified distributions (dianomai) |

Unknown |

|

78 |

IG XII.5 667 ll. 10-21 |

Syros |

251 CE |

Apollonides |

10 denarii each to the gerousiastai and 1 denarius to the women, free maidens, and attendants of the stephanephoroi on the first day of his stephanephoria; 2 denarii each to the gerousiastai and 1 denarius to all others on the second day of his stephanephoria |

Denarius |

|

79 |

IGBulg I2 15bis ll. 5-9 |

Dionysopolis |

Early 3rd century CE |

M. Aurelius [---]koros |

Conducted distributions (dianomai) to the councillors, councillors from other cities of the Pentapolis, merchants, doctors, and teachers |

Unknown |

|

80 |

IGBulg I2 16 ll. 7-9 |

Dionysopolis |

Early 3rd century CE |

M. Aurelius Demetrios |

Unspecified distributions (dianomai) to the council at the consecration ceremony for his statue |

Unknown |

|

81 |

SEG 43.718 ll. 21-24 |

Iasos |

Early 3rd century CE |

M. Aurelius Daphnos |

Made a distribution (nome) to the councillors |

Unknown |

|

82 |

I.Prusias ad Hypium 6 ll. 10-11 |

Prousias-under-Hypios |

Early 3rd century CE |

M. Domitius Candidus |

Unspecified distributions (nomai) |

Unknown |

|

83 |

SEG 54.724 ll. 24-26 |

Rhodes |

Early 3rd century CE |

Unknown |

5 denarii each to the citizens, 10 (?) denarii to the councillors |

Denarius |

|

84 |

I.Aphrodisias 11.110 ll. 14-29 |

Aphrodisias |

3rd century CE |

Father of M. Aurelius Polychronios |

Donated 1,670 denarii towards annual distributions (kleroi) to the council by lot at his statue, with 200 councillors to receive 6 denarii each |

Denarius |

|

85 |

I.Iznik 61 ll. 7-8 |

Nikaia |

3rd century CE |

Onesimos |

4 Attic drachmas to each gerousiastes |

Attic drachma |

|

86 |

I.Iznik 62 ll. 2-4 |

Nikaia |

3rd century CE |

Unknown |

Distribution of unknown amount to each gerousiastes |

Unknown |

|

87 |

SEG 65.655 ll. 5-18 |

Rhodes |

3rd century CE |

M. Aurelius Kyros |

Donated 20,000 denarii towards annual distributions to the summer and winter councillors; 10 denarii each to the councillors and 5 denarii to the citizens during the inauguration of his statue |

Denarius |

|

88 |

I.Selge 17 ll. 20-21 |

Selge |

3rd century CE |

Unknown |

Mention of distributions (dianomai) to the councillors, ekklesiastai, and their children |

Unknown |

|

89 |

I.Stratonikeia 309 ll. 9-13 |

Stratonikeia |

3rd century CE |

Claudius Ulpius Aelius Asklepiades and Ulpia Aelia Plautilla |

2 denarii each to women during the procession of the god, and 5 denarii to all citizens and foreigners in lieu of a public meal |

Denarius |

|

90 |

IG XII.5 141 ll. 6-8 |

Tenos |

3rd century CE |

Unknown |

8 denarii each to the councillors and patrobouloi, 2 denarii to the citizens and other inhabitants |

Denarius |

|

91 |

TAM V.2 926 ll. 8-13 |

Thyateira |

3rd century CE |

P. Aelius Aelianus |

Donated 560 denarii towards an annual distribution of 1 denarius to each councillor on his son’s birthday |

Denarius |

|

92 |

I.Tralleis und Nysa I 145 ll. 16-19 |

Tralleis |

1st-3rd centuries CE |

Ti. Claudius Claudianus |

Donated a sum towards an annual distribution of 250 denarii to each councillor on his birthday |

Denarius |

|

93 |

I.Aphrodisias 11.403 l. 6 |

Aphrodisias |

1st-4th centuries CE |

Zenon |

Donated 5,000 denarii towards distributions (kleroi) |

Denarius |

|

94 |

TAM V.2 939 ll. 7-13 |

Thyateira |

1st-3rd centuries CE |

Artemidoros |

Donated gardens towards annual distributions (dianemesthai) to the councillors |

Unknown |

|

95 |

TAM V.2 1197 ll. 8-9 |

Apollonis |

Imperial period |

Unknown |

Donated a sum towards annual distributions (dianome) to the council on his birthday |

Unknown |

|

96 |

IG IV 597 ll. 9-13 |

Argos |

Imperial period |

Onesiphoros |

4 denarii each to the citizens, 2 denarii to other free individuals |

Denarius |

|

97 |

IGBulg I2 63bis ll. 10-15 |

Dionysopolis |

Imperial period |

Claudius Akulas |

10 Attic drachmas each to the councillors, new citizens, and visiting soldiers in lieu of a public meal |

Attic drachma |

|

98 |

I.Ephesos 644 ll. 8-9 |

Ephesos |

Imperial period |

Ti. Claudius Prorosius Phretor |

Distributed an unknown amount to the citizens |

Unknown |

|

99 |

I.Didyma 297 ll. 8-12 |

Miletos |

Imperial period |

Unknown |

Distributed an unknown amount of denarii to the council on the god’s birthday |

Denarius |

|

100 |

IGR III 492 ll. 11-14 |

Oinoanda |

Imperial period |

Licinnius Longus |

2 denarii to each of the 500 (councillors?), 250 denarii (?) to named boys and girls |

Denarius |

|

101 |

TAM II 1200 ll. 18-21 |

Phaselis |

Imperial period |

Ptolemaios son of Kolalemis |

Bequeathed money towards distributions (dianomai) |

Unknown |

|

102 |

TAM V.3 1476 ll. 11-16 |

Philadelphia |

Imperial period |

L. Antonius Agathopous |

Donated 1,500 denarii and 300 denarii for annual distributions to the councillors and gerousiastai |

Denarius |

|

103 |

SEG 19.835 ll. 3-6 |

Pogla |

Imperial period |

P. Caelius Lucanus |

Conducted distributions (dianomai) to the citizens, councillors and gerousiastai over a number of years |

Unknown |

|

104 |

Robert, La Carie II 172 ll. 12-15 |

Sebastopolis |

Imperial period |

Unknown |

1 denarius to each citizen, 1 denarius and 3 assaria to each councillor |

Denarius, assarion |

|

105 |

I.Side 103 ll. 6-8 |

Side |

Imperial period |

Daughter and son of a Kneis |

Distributed 5,000 denarii to the council |

Denarius |

|

106 |

TAM II 191 ll. 7-9 |

Sidyma |

Imperial period |

Theages |

Donated 3,000 drachmas (?) towards an annual distribution (epidosis) to the citizens |

Unknown |

|

107 |

I.Stratonikeia 352 ll. 3-6 |

Stratonikeia |

Imperial period |

Unknown |

1 denarius to each woman |

Denarius |

|

108 |

I.Tralleis und Nysa I 220 ll. 1-16 |

Tralleis |

Imperial period |

Soterichos |

Donated an amount for annual distributions to the council on his birthday, with mention of 9 assaria |

Assarion |

|

109 |

I.Aphrodisias 13.5 ll. 15-18 |

Aphrodisias |

Imperial period |

Demetrios son of Pyrrhos |

Donation of money towards perpetual distributions (kleroi) |

Unknown |

References

Amandry, M., 2021, «Rome et les monnayages de Grèce centrale, Attique, Péloponnèse et Crète», in: R. H. J. Ashton, N. Badoud (eds.), Graecia capta? Rome et les monnayages de l’Egée aux IIe-Ier s. av. J.-C., Fribourg, 101-110.

Amandry, M., & S. Kremydi, 2017, «La pénétration du denier en Macédoine et la circulation de la monnaie locale en bronze (IIe siècle av. J. C.-IIe siècle apr. J. C.)», in: M. G. Parissaki, J. Fournier (eds.), L’Hégémonie romaine sur les communautés du Nord Égéen (IIe s. av. J.-C. – IIe s. apr. J.-C.). Entre ruptures et continuités, Athens, 79-115.

Ameling, W., 2004, «Wohltäter im hellenistischen Gymnasion», in: D. Kah, P. Scholz (eds.), Das hellenistische Gymnasion, Berlin, 129-161.

Ashton, R. H. J., 1994, «The Attalid Poll-Tax», ZPE 104, 57-60.

Ashton, R. H. J., & A.-P. C. Weiss, 1997, «The Post-Plinthophoric Silver Drachms of Rhodes», NC 157, 1-39.

Azoulay, V., 2017, Pericles of Athens, Princeton.

Baker, P., & G. Thériault, 2018, «Xanthos et la Lycie à la basse époque hellénistique: Nouvelle inscription honorifique xanthienne», Chiron 48, 301-331.

Beck, M., 2015, Der politische Euergetismus und dessen vor allem nichtbürgerliche Rezipienten im hellenistischen und kaiserzeitlichen Kleinasien sowie dem ägäischen Raum, Rahden.

Boehringer, C., 1997, «Zu Chronologie und Interpretation der Münzprägung der Achaischen Liga nach 146 v. Chr.», Topoi 7.1, 103-108.

Boubounelle, O., C. Bady & A. Vlamos (eds.), 2023, Les Grecs face à l’imperium Romanum. Résilience, participation et adhésion des communautés grecques à la construction d’un empire (IIe s. av. – Ier s. de n.è.), Besançon.